Like many in her age group, Jenny Li, a 38-year-old who works in retail planning, recently found herself serving as counselor and advisor to her parents, who were approaching age 65 and preparing to go on Medicare.

Like many in their age group, Li’s parents were not well versed on the program, but they had heard the ubiquitous sales pitches for Medicare Advantage. They were on the verge of signing up, unaware that the MA landscape is fraught with scams and deceptive sales practices designed to obfuscate and confuse.

Today a large number of seniors don’t know that only traditional Medicare allows you to go to any doctor at any time. Along with a supplemental policy called Medigap, this combination covers virtually all medical bills without the restrictions that come with MA plans. However, because of the federal government’s role in backing the growth of MA plans, as well as continuous promotion by the private health insurance industry itself, Medicare Advantage now accounts for more than half of the Medicare market.

Over the past several years, seniors have been encouraged to drop their traditional Medicare coverage in favor of MA plans. And for years, the government has overpaid the health plans, which enabled them to entice seniors with gym memberships, groceries, and some dental and vision care that traditional Medicare isn’t allowed to offer. In effect, the Medicare market is now the proverbial uneven playing field thanks to the federal government under the leadership of both Democrats and Republicans.

The complexities of one of the country’s few social insurance programs have bedeviled seniors since Medicare’s inception in 1965. From the beginning, the program has been plagued by scam artists with sales tactics designed to mislead, confuse and entrap seniors.

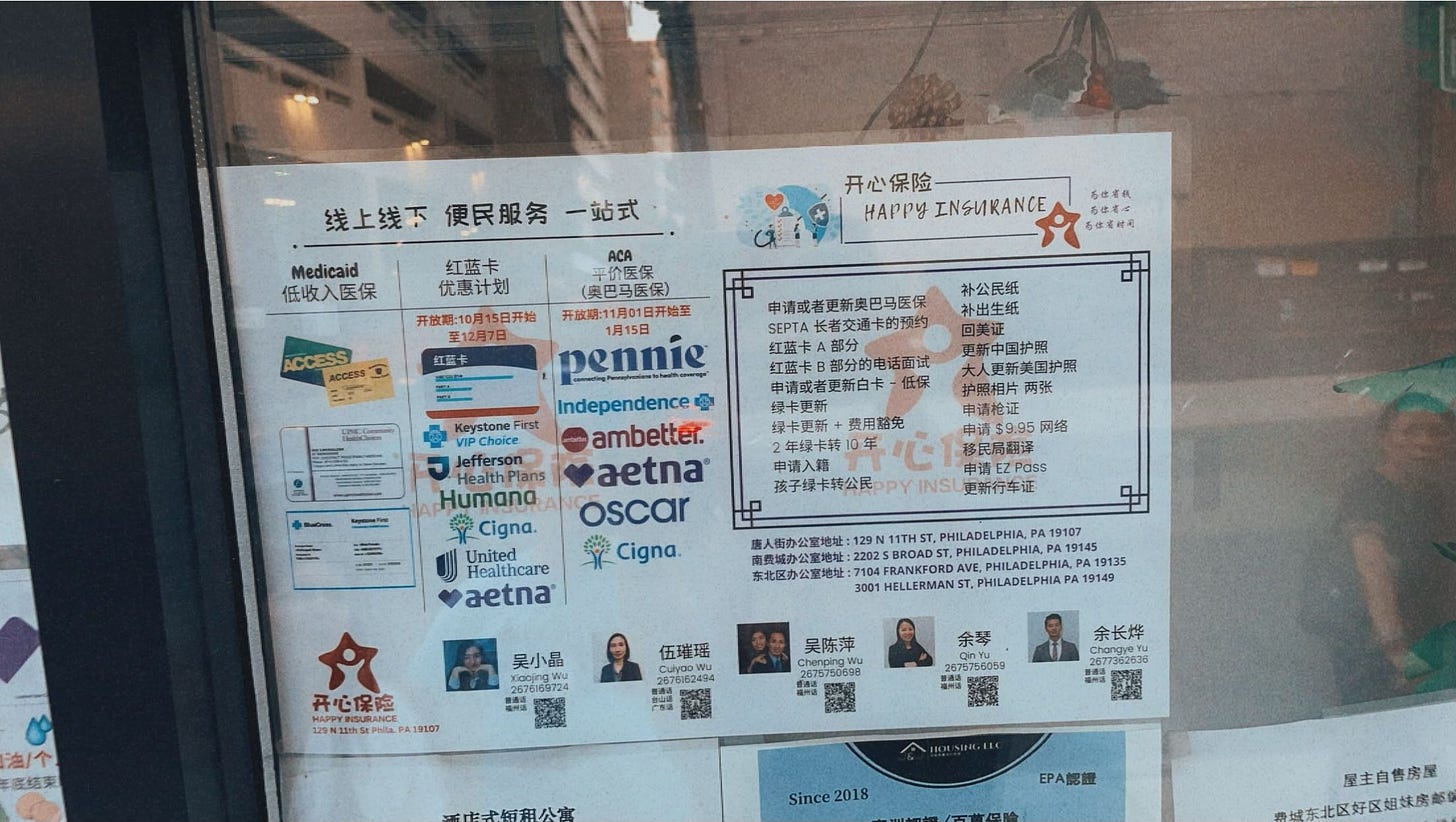

Li did not want her parents trapped in an Advantage plans provided by a profit-making insurance company. While it’s possible to return to traditional Medicare, there’s a catch: After you enroll in an MA plan, you can no longer buy a Medicare supplement policy without what’s called “underwriting,” a practice that means insurers will investigate your medical history and offer affordable coverage only to those in excellent health. In a few states, you might be able to get a supplement during certain times of the year, but the only states where you can buy a supplement anytime regardless of your health are Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York. Since Li's parents live in Pennsylvania, they wouldn’t have that escape. She decided to pay the monthly premium for supplement plans, which now cost $147 for her mom and $166 for her dad. At first, her mom resisted. Why would you pay for something that’s free, she argued? In their close-knit Chinese community they had heard a lot about MA plans that came with no premiums.

While MA sales pitches emphasize that in most cases there are no upfront premiums, the plans are not free. Those who sign up are likely to encounter high deductibles usually not discussed during sales presentations and not mentioned in TV promotions, especially if they seek care outside of their health plans' limited provider network.

To get a flavor of current out-of-pocket limits, I consulted the “Medicare and You Handbook” for New York City and found a Humana preferred provider plan for a New York City ZIP code with out-of-pocket limits ranging from $9,350 to $14,000. The limits for a UnitedHealthcare AARP Medicare Advantage PPO plan ranged from $8,900 to $14,000.

It wasn’t easy for Li to convince her parents not to sign up.

“I don’t think they knew it was Medicare Advantage. They thought it was part of Medicare,” Li said.

“When they became eligible for Medicare, it was a foreign system to them. Whatever they can save, they do. If they could buy something in the middle price range, that’s what they did. Medicare Advantage was the middle-of-the-road option for them. My mom was adamant this was Medicare.”

Li decided to pay the premiums on her parents’ supplement policies when she learned they could have trouble buying Medicare supplement policies later on.

That turned out to be a lucky decision. Four years after she bought the Medigap policies, her father required triple heart bypass surgery. “Everything was covered [under traditional Medicare],” Li said, except for deductibles of $1,872. “It was so easy.”

A few years ago I asked a St. Louis woman to keep track of what goodies her Medicare Advantage plan offered throughout the year. Her experience was instructive. She told me the promised benefits were pretty skimpy, and the dental benefit paid so little her husband ended up using a dental benefit that his former employer had provided. What do you want your insurance to do: pay for a necessary heart bypass, or give you a bag of gifts along with potential fights with an insurance company to pay for a major illness?

But sales pitches are persuasive. I once attended an insurance company sales event at a coffee shop. At the end of the program, one man refused to talk to me. He was in a hurry, he said, because he might lose his chance to sign up for a Medicare Advantage plan.

I did all the research and quickly came to the conclusion that MA was not for us. The gap plan wasn’t very costly BUT, that will increase every year and I worry it could get unaffordable at some point. I suspect a lot of people have no choice but to go MA because they can’t afford the gap plans, but then get screwed with OOP costs. Such a mess.

This is great info. Are there other resources that explain the pitfall of MA plans? And do all users need supplemental Medicare policies?