The Sunlight Report on UnitedHealth Group

The Sunlight Report on UnitedHealth Group is a first-of-its-kind look at the nearly 2,700 subsidiaries that make up UnitedHealth Group, the largest health care conglomerate in the world.

“It’s what keeps him up at night.”

I heard those words early last year from a top Department of Justice official during a briefing about the priorities of the DOJ’s Antitrust Division. Those of us in the room were told that one of the things that most worried Jonathan Kanter, who led the antitrust work for the Biden administration, was the growth, through rapid vertical integration, of big health insurers, UnitedHealth Group in particular.

Around the same time, several blocks up Pennsylvania Avenue, at the Capitol, a conservative Republican congressman from Georgia began calling for the breakup of UnitedHealth. Representative Buddy Carter, who would soon chair the Subcommittee on Health of the powerful Energy and Commerce Committee, wrote on X last year that “UnitedHealth owns 10% of all doctors in the United States. It’s time to bust up this monopoly.”

A few months earlier, we at HEALTH CARE un-covered had published a story about UnitedHealth’s most notable acquisitions since it became a publicly traded company in 1984 — transactions that catapulted the Minnesota-based company from relative obscurity as recently as the 1990s to the top ranks of American corporations. Last year, UnitedHealth took in more than $400 billion in revenues and ranked #4 on the Fortune 500 of U.S. companies. Only Walmart, Amazon and Apple are bigger.

As revealing as our December 2023 story was, we knew we had only scratched the surface. The fact is, UnitedHealth comprises far more subsidiaries, in far more categories than our initial reporting had uncovered. That’s because we had only found the acquisitions the company had announced or the media had learned about (or that a Google search could find). We suspected that few people – in Washington, D.C., or elsewhere – including Kanter and Carter, had any real sense of the vast scope and reach of this single company.

Our reporting caught the attention of Arnold Ventures, a major U.S. philanthropy. In early 2024, they asked if the Center for Health and Democracy (CHD), an organization that I run, would be interested in doing a much deeper dive into the ever-expanding and already enormous, monopolistic conglomerate that UnitedHealth has become. What we found was stunning: This company that we think of as an insurer has used our premiums and tax dollars to buy its way so deep into health care delivery and also into data collection – and sales, marketing and health care information – that people at UnitedHealth companies know more about us (and how to influence us) than even our closest friends.

In fact, the company’s tentacles now extend so deeply into non-insurance businesses that UnitedHealthcare, the original insurance division, now contributes less to the company’s overall profits than its pharmacy, clinical, data and other operations. One could argue that UnitedHealth has become a 21st-century version of Standard Oil, the John D. Rockefeller conglomerate the Supreme Court ordered broken up in 1911.

How United structures itself and operates is confusing and seemingly designed to obscure and obfuscate. The company no longer issues a press release to announce any but the biggest acquisitions. Ironically, it is now so big it doesn’t have to do that, and company executives likely decided long ago that telling us about its many deals would not be good PR, that the less we (and Congress, the Justice Department and regulatory bodies) know about what they’re up to, the better. That and the fact that announcing them one by one would keep UnitedHealth’s PR team too busy. They would have had to churn out an acquisition press release just about every day in recent years if they were legally required to do so.

Unfortunately, no law or regulation makes companies disclose every significant deal in a manner that most of us would ever see. Publicly traded companies like UnitedHealth are required by the Securities and Exchange Commission to disclose to shareholders and regulators any transaction that could be considered “material to earnings.” As a company gets bigger, that bar gets higher. Generally, the SEC requires a company to announce an acquisition when certain thresholds are crossed. Disclosure is mandatory

if the assets of the company being bought exceed 20% of the acquiring company’s total assets;

if the investment in the company being acquired exceeds 20% of the acquiring company’s market capitalization; or

if the earnings of the acquired company exceed 20% of the acquiring company’s income.

As I write this, UnitedHealth’s market cap is north of $275 billion. (It had been as high as $450 billion before investors began questioning the company’s ability to withstand all the scrutiny and headwinds the company is now facing.) That means that until recently, the company probably wouldn’t have had to disclose an acquisition of less than $90 billion. When you consider that just a hundred or so U.S. companies have a market cap of $90 billion or more, you can understand why you’ve never heard about most of UnitedHealth’s many, many deals in recent years and likely have no idea how involved in our lives this beast of a company has become.

Yet it is becoming increasingly likely, as Representative Carter noted, that even your doctor is now on UnitedHealth’s payroll. I hope you will understand why you and everybody else in this country should care about that. As someone who worked for two big insurers over nearly 20 years, I can assure you that every employee, including the ones with an MD or RN after their names, knows they have to do their part to help UnitedHealth meet Wall Street’s relentless profit expectations. That goes for the doctors and nurses who treat you in their offices as well as the thousands you’ll never see but who make the initial decisions from their cubicles or kitchen tables, often in foreign countries and increasingly using AI, whether or not you’ll get the care you need.

Here are some of the highlights and analysis from CHD’s Sunlight Report on UnitedHealth Group (Note: the best way to dive into the full report is on desktop rather than mobile), which is being published today with financial support from Arnold Ventures:

As of the third quarter of 2024, UnitedHealth Group was composed of 2,694 subsidiaries across a broad range of categories.(Note it could now be more than 3,000. STAT News recently reported that the company bought or created 250 additional entities last year. Or it could be less. As Bloomberg reported yesterday in a blockbuster report, the company made some "stealth sales" at the end of 2024 "that helped UnitedHealth beat Wall Street targets." More to come from us on that in the coming days).

UnitedHealth grew so big it could have bought CVS Health, which owns Aetna and operates close to 10,000 stores, or Cigna, where I used to work, without meeting the SEC’s market capitalization threshold for disclosure purposes. Cigna and CVS have market caps of around $81 billion and $82 billion respectively. They, too, have become enormous conglomerates after buying their way into health care delivery and the pharmacy supply chain, ranking 6th and 16th, respectively, on the Fortune 500 list of U.S. companies, but they are dwarfs compared to UnitedHealth.

UnitedHealth now owns such big chunks of the U.S. health care system that it can influence whether millions of us can get the care we need, where we will get it, and how much we’ll have to pay for it, including for our medications – even if we are not enrolled in a UnitedHealthcare plan – from our cradle to our grave.

The nearer we get to our graves, the more likely UnitedHealth will be in our lives – or what is left of it. Many of the company’s most recent acquisitions have been in the home health and hospice space.

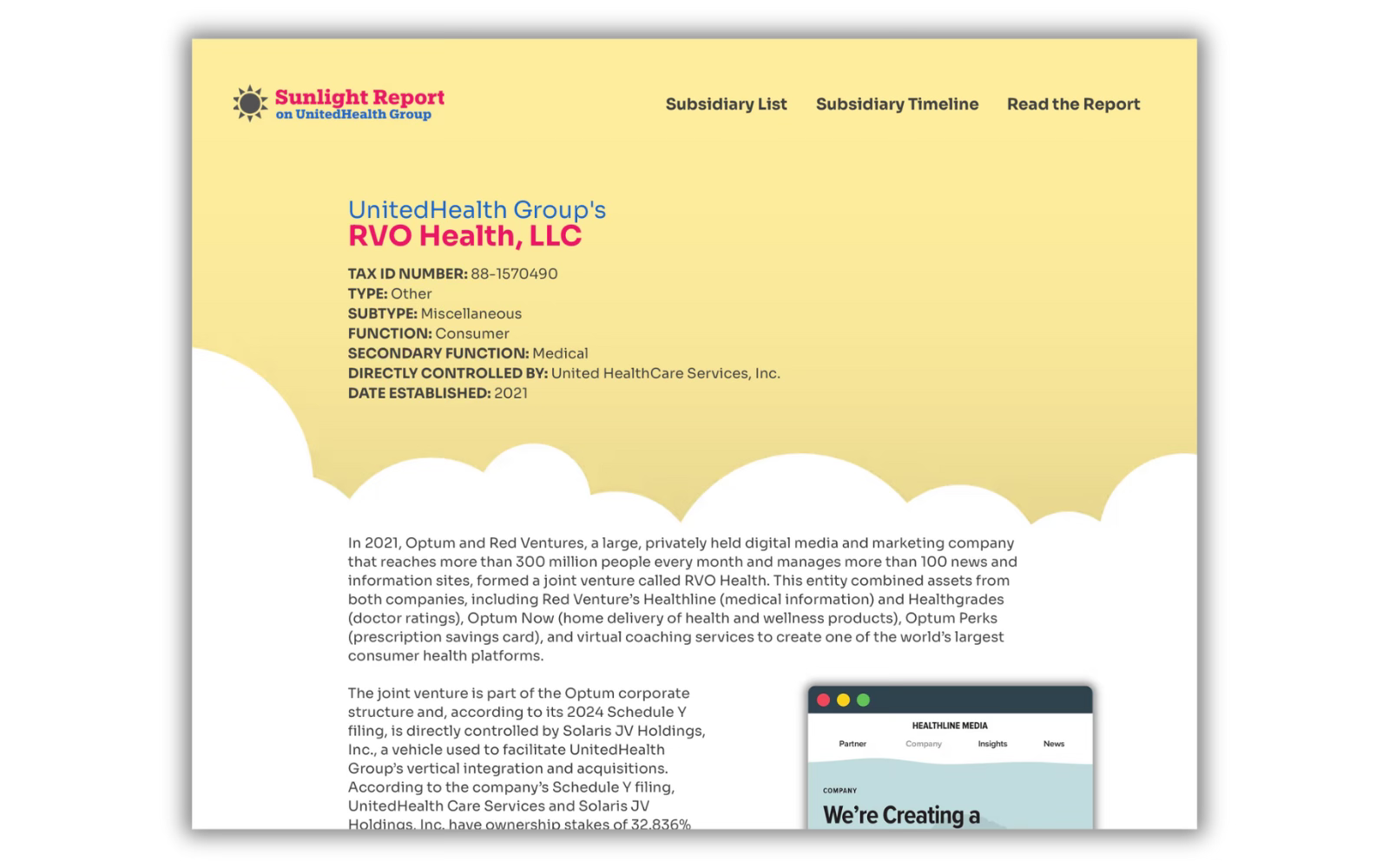

The company increasingly even controls much of the information we have available to us online about medical care and health insurance. One of its transactions created RVO Health, which is now a massive, privately held digital media and marketing company that reaches more than 300 million people every month and manages more than 100 news and information sites.

It owns and operates numerous companies in the insurance agent and brokerage space, including online outfits like Healthmarkets that appear to be independent resources for health insurance plans in the individual and group markets.

Most of UnitedHealth’s acquisitions by far have occurred since 2010, and most by far have been in the clinical category, not the insurance category. That is likely at least partly because of a well-intended provision of the Affordable Care Act, which was passed in 2010, that requires insurers to spend no less than 80-85% of our premiums on our medical care (80% in the small group market and 85% in the large group market). If an insurer doesn’t spend that much, it must send rebate checks to its customers. Because that ACA provision applies to health insurance but not health care delivery, owning physician practices, clinics and other clinical operations provides a way to work around that requirement and the need to issue rebate checks.

UnitedHealth is now about as multinational as a company can get, with operations of one nature or another in just about every country. It even owns and operates hospitals abroad, something it doesn’t do in the U.S. – at least not yet.

The CHD team suspected this project would take a few weeks, if not a few months, because of the sleuthing that would be required and then the task of categorizing and visually showing what we found. For a while, we thought it might even be impossible because of the opacity of the company. Fortunately, we remembered that health insurance companies have to file something called a Schedule Y with regulators in states where they do business. U.S. states use insurers’ Schedule Ys to help them determine if the companies meet transparency, solvency and other compliance requirements.

Schedule Ys contain a treasure trove of information and, for conglomerates like UnitedHealth Group, are massive documents. Among other things, companies must list all of their subsidiaries and note where the various entities are headquartered (in UnitedHealth’s case, frequently in Delaware, where taxes are low, and often offshore) and how much control the parent company has. While the disclosures don’t include the date a subsidiary was acquired or created, you can figure that out by reviewing the Schedule Ys a company filed over a span of years, which is what we did, starting in 2010. (CHD’s researchers couldn’t track down UnitedHealth’s Schedule Ys before 2010, but subsequent filings disclosed previous acquisitions and business entity creations.) If an entity made its first appearance on a 2020 Schedule Y, for example, CHD decided to report in a timeline that it was added to the company’s roster in 2020 (although it is possible it could have been added late in 2019 after UnitedHealth filed its 2019 Schedule Y).

Paying Itself and Circumventing Congressional Intent

Why has the company spent so much money buying clinical operations? Well, for one thing, the U.S. health insurance market has been stagnant for years, and it’s not where the big bucks and bigger profit margins are in health care. As health insurance companies have jacked up their premiums over the years – an employer-sponsored family policy now costs more than $35,000 on average, triple what it cost in 2005 – more and more small employers have thrown in the towel and stopped offering subsidized coverage to their workers. As we reported last year, UnitedHealth actually insured fewer people in its commercial (individual and employer-sponsored) plans in 2023 than it did in 2013, even though the Affordable Care Act made coverage more available and affordable for many people. Before vertical integration became an industry-wide strategy around the time the ACA was passed, big insurers grew by “stealing market share” from each other and by buying their smaller competitors. Which is what they did during much of the 1990s and early 2000s. But now, because of consolidation, there are very few smaller competitors left to buy, and regulators have refused to approve bigger insurance company deals, like the proposed Cigna-Anthem merger or Aetna’s proposed acquisition of Humana from a few years ago.

That’s why UnitedHealth and a handful of other big insurers have spent so much money to entice American seniors into the Medicare replacement plans they market as Medicare Advantage. All of UnitedHealthcare’s health plan enrollment growth between 2013 and 2023 occurred in the Medicare Advantage plans it markets with AARP and the Medicaid programs it manages for several states. But even in those programs, the growth is limited. And Wall Street demands continuous – and profitable – growth.

Back to that provision of the ACA that requires insurers to spend at least 80% of our premiums on our care. The provision is in the ACA because before 2010, insurers were spending less and less of our premiums on our care and pocketing more and more of our money – or sending it to shareholders. That’s why I said the provision was well-intended. Several states had enacted similar requirements in previous years.

But as I noted, the ACA’s requirement applies only to health insurance, not health care delivery. By owning physician practices and other clinical operations, including pharmacy benefit managers, UnitedHealthcare can make billions in profits outside of health insurance and also more easily meet the ACA’s requirement by adjusting what it pays the physician groups and other clinical operations it now owns and steering its health plan enrollees to those operations. And buying clinical and other businesses has proven to be less likely to trigger an antitrust review by regulators.

UnitedHealth’s Optum Division Now Generates More Profits than Health Insurance

Also, the more clinical assets UnitedHealth owns, the more it can pay itself, albeit with our premiums and tax dollars. If you look at the company’s 2024 financials, you’ll see that the company reported total revenues of $400.3 billion (more than four times the $94.2 billion it reported in 2010). If you drill down, you’ll see that UnitedHealthcare, the insurance arm, collected $298.4 billion in revenues in 2024 while its faster-growing sibling, Optum, which houses the clinical operations, collected $253 billion. If you add those up, you get $551.4 billion.

So what gives? Well, the $150.9 billion difference (between $551.4 billion and $400.3 billion) is accounted for in what UnitedHealth Group discloses in its annual filings with the SEC as “intercompany eliminations.” In other words, that $150.9 billion is what the company’s left hand (UnitedHealthcare) paid its right hand (Optum) and consequently had to be excluded from total revenues.

Since the ACA became law in 2010 and UnitedHealth Group hit the accelerator on its vertical integration strategy, the company’s “eliminations” have increased from $18.3 billion (or 16.2% of 2010 revenues) to $150.0 billion (27.2% of 2024 revenues). In various ways, the company can steer its nearly 50 million health plan enrollees to health care delivery operations it owns while paying an ever-diminishing percentage of its health plan revenues to health care providers it doesn’t own or control.

Another way of looking at this is that nearly 60% of Optum’s $253 billion in revenues last year came from the holding company’s other big division, UnitedHealthcare. And even though Optum’s revenues were lower than UnitedHealthcare’s, it made more money last year for the parent. Of UnitedHealth Group’s $32.3 billion in 2024 profits, 52% ($16.7 billion) was contributed by Optum.

Making Wall Street Happy

As the company snapped up larger and larger chunks of health care delivery over the years, its stock price skyrocketed. If you had bought a share of stock in the company at the beginning of 2010, it would have cost you $25.10. If you held on to it until the beginning of 2024, it would have been worth $528.77, an increase of 2000%. The company’s top executives, who are paid mostly in stock grants and options, and the large institutional investors that own most of UnitedHealth’s stock, grew richer and richer as the company ballooned in size. As a former insurance company executive myself, I can attest to the inordinate attention a company’s C-Suite pays to stock price. It explains why people who run big insurers skim millions from our premiums every year to elect politicians they can count on to vote the way they want on legislation that could affect profits and stock price and why insurers are among the top spenders on lobbying in Washington and state capitals. According to OpenSecrets, UnitedHealth alone has doled out nearly $35 million in campaign contributions since 1990 and has spent more than $105 million to lobby elected officials and regulators since 1998.

How to Explain What We Found

As you can imagine, UnitedHealth’s Schedule Ys got longer and longer with each passing year, and we had to review them all. And then we had to figure out how to display what we found in various ways to show not only how quickly the company has grown but also where its tentacles have extended into health care delivery – and not just in this country. Our international readers, even those in countries with single-payer health care systems like Canada, will see that they, too, likely are contributing, probably unknowingly, to UnitedHealth’s fortunes.

Rather than make this piece even longer, I encourage you to visit the Sunlight Report yourself to see what UnitedHealth has become. Should Congress, the Trump administration’s Department of Justice (which The Wall Street Journal reported in May has opened a criminal investigation into the company’s Medicare operations) and the courts take steps to “bust up” the company, as Representative Carter suggests? If not, why not? What would allowing UnitedHealth to keep extending its tentacles into every aspect of our health care system mean for us and future generations?

Let us know after you read the report if an even bigger UnitedHealth keeps you up at night, too. And, if you are interested in learning more about how to use this report to advance your fight for a better health care system, sign up here to get connected with the CHD Advocacy Team and join us in shedding light on America’s biggest health care conglomerate.

An excellent report. I appreciate the invitation to read the full result in the Sunlight report, and to provide my opinion of its content, but realistically I am neither qualified to interpret the figures and charts found therein, or have the time to do so. What I would appreciate instead, is some guidance on how to go about raising this issue to the correct decision makers in government and to elected officials at both the state and federal level demanding action. That I can do.

This was an eye-opening piece. Thank you not only for the article but for all the work that went into it.

What I find ironic is that while Americans are opposed to a single-payor healthcare system, with Unitedhealth Group that's what we're increasingly getting.