‘Moral Injury’ Enters Health Care Lexicon

Nurses and other caregivers join doctors in using the term as resources and autonomy disappear.

Psychiatrist Wendy Dean remembers not only the “Eureka moment” but exactly where she was – “I was weeding in my garden” – when a National Public Radio report about the stress faced by U.S. military operators of deadly drones triggered a revelation. That’s when she realized that the emotional exhaustion of so many physician colleagues she spoke with went well beyond “burnout.”

The resulting article that Dr. Dean and co-author Dr. Simon G. Talbot published in STAT News in July 2018 – headlined “Physicians aren’t ‘burning out.’ They’re suffering from moral injury” – is still one of that site’s most widely read articles. Their report – arguing that it wasn’t overwork but the inability to balance the best treatment for patients with the economic pressures of modern health care that was stressing out doctors – sparked a conversation and controversy.

Today, not only is the phrase “moral injury” widely accepted by physicians, who saw the monetary contradictions of their business taken to new heights by the COVID-19 pandemic, but the concept is rapidly spreading among nurses, hospital aides, medical staff, and other workers with similar frustrations.

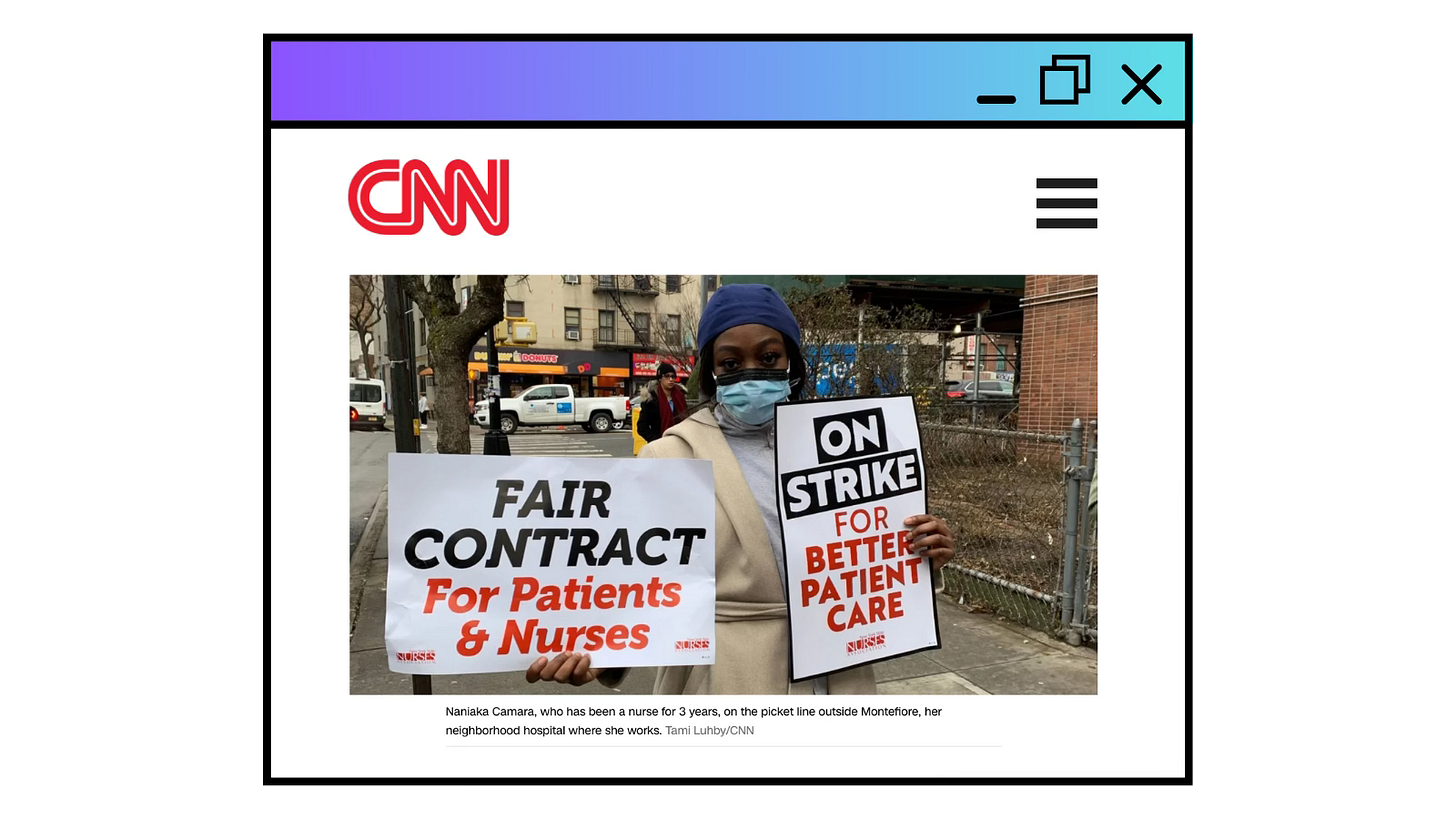

In recent months, thousands of unionized nurses and other health care workers have walked off the job – not just seeking higher pay but improved working conditions on hospital floors that are short-staffed or lack proper equipment. The strikers argue that cost-cutting creates a crisis of patient care that undercuts why they entered their profession.

“When a registered nurse knows the level, the quality of care that they are able to provide a patient, but they are unable to provide that level of care because of unsafe staffing levels and working conditions, that causes deep moral injury,” said Amirah Sequeira, national government relations director of National Nurses United, at a recent health care summit sponsored by Politico. She used her appearance to endorse a proposed California law that would increase the number of nurses on duty at hospitals when caseloads spike.

The growing embrace of the “moral injury” concept by nurses comes as no surprise to Dean, who said she started getting emails at 6 a.m. the morning the STAT article was published six years ago, from health care professionals whose reaction was, ‘Oh my gosh, this is the language that I’ve been looking for the last 30 years!’ She said the conversation resonated not just with nurses, physical therapists, mental health professionals and social workers – but outside of medicine, with people such as public defenders, all overwhelmed by the moral contradictions of their work.

Recent news stories have focused on private-equity-owned Steward Healthcare pushing its hospitals to the brink of insolvency while nurses complain that critical equipment is being repossessed by unpaid vendors. Doctors are increasingly fighting big insurance companies over prior authorization denials of procedures or medications they believe their patients need to get healthy.

Dean, who eventually partnered with co-author Talbot to form the nonprofit Moral Injury of Healthcare to raise awareness about the problem and possible solutions, said most doctors and nurses believe strongly in the Hippocratic Oath to “do no harm” to their patients, yet feel that vow is compromised by some private-equity investors and big insurance companies.

Dean worked for the U.S. Department of Defense during the 2010s around soldiers recovering from war injuries. When she talked with colleagues about their moral frustrations, she began to connect their problems with then-growing awareness about various forms of post-traumatic stress. She said the definition of moral injury as “perpetrating, bearing witness to, and learning about acts which transgress our deeply held moral beliefs” struck a chord with what doctors and others were telling her about working in corporate health care.

Now, nurses’ adoption of the moral injury concept has coincided with an explosion in labor unrest at the nation’s hospitals and related facilities. The number of strikes in the industry more than doubled from 15 in 2021 to 36 last year, even as disruptions related directly to the pandemic decreased.

“Sometimes I feel like what I did was pointless,” Naniaka Camara, a nurse at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, told CNN after joining 7,000 New York City nurses on the picket line. “I’m apologizing for stuff that has nothing to do with me” – referring to delays in giving patients their medication because her hospital was so severely understaffed.

“During the height of COVID, what felt like despair, fear, and suffering transformed into an unapologetic refusal to accept the status quo,” said Kelly Nedrow, the senior director for health issues for the American Federation of Teachers. While best known for its education work, the AFT also represents some 250,000 health care workers, primarily registered nurses. Nedrow said in an interview that she frequently speaks with her members who go home from their shifts in tears over frustrations like broken equipment that they blame on corporate cost-cutting. A few members have succumbed to suicide.

Nedrow said that’s why she and other health care advocates and activists have increasingly adopted the moral injury framing as they push for new contracts that enshrine better working conditions, or for legislation at the state level to require minimum staffing levels or other hospital reforms. The AFT leader said there’s no question that the root cause of this crisis is “financialization” in health care and “the extraction of money to line the pockets of financial interests – purchasing land and leasing it back to hospitals, those kinds of practices” – that have nothing to do with patient care.

Dean agreed that the growing wave of labor activism in the health care field – including an increasing number of physicians who are unionizing – is closely linked to a growing understanding that what clinicians had long labeled as “burnout” was less about overwork and more about the outside pressures that have been creating such a stressful work environment.

“When you tell somebody they're burned out, it’s about them,” Dean said. “It’s about their inability to cope, their inability to be resilient enough or resourceful enough. It is about their failing in some way. When you talk about moral injury it says to them this isn't about you, it’s about the places and ways you’re being asked to work.”

That revelation, Dean said, is what is currently empowering health care workers to fight aggressively for change.

Dean’s Moral Injury of Healthcare group and labor leaders are urging Congress and other federal and state agencies to investigate the anti-competitive practices that are at the heart of the industry’s increasing financialization. They are also urging lawmakers on Capitol Hill to reauthorize a program that provides federal support to health care workers struggling with mental health issues.

The prior authorization practices of insurance companies is central to the fight over moral injury. Indeed, Dean traces a lot of the psychological stresses on doctors to a fundamental change in their relationship with insurers, as more doctors shifted from mostly solo practices to working for private companies – and the loss of control that entrails. She explained that doctors lost their former power to simply walk away from insurance companies that reject too many procedures because most of their privately insured patients are in employer-sponsored plans and employers, she said, “are very loath to push back on insurers.”

The powerful American Medical Association (AMA) is lobbying to sharply curtail if not eliminate prior authorization requirements, and the movement is gaining traction in a growing number of state legislatures, even as a federal bill remains stuck in the current gridlock in Congress.

Dean believes there are other ways to minimize the crisis of moral injury. She said that rewards for workplaces where doctors and nurses are thriving – hospitals with higher-than-average retention rates, for example – could include higher Medicare reimbursement rates. She also proposed that predatory or problematic health care executives could be tracked in a national data bank, as is currently done for physicians with poor disciplinary records. Dean is hopeful that agencies like the Federal Trade Commission will increase their regulation of abusive practices in the health care field.

Despite stiff headwinds in an industry that can be hostile to reform, Dean said she’s delighted to see the idea of moral injury that began with the lightbulb moment in her garden taking root in the national debate over fixing health care. “We don't have 20,000 pitchforks in the street but we have changed the conversation,” she said. “We have changed the lexicon of health care.”

Having spent some time on the care delivery side, the pressure on our providers has been building since the late '80s. There was the LOS and census management consultants that "cut to the bone" nurse staffing and shift management. This occured in non-profit and for-profit facilities. Now, almost 40 years later, our corporatization of care at every turn has created a crisis for the care provider. We need to remove the profit incentives that have plagued health care and return the delivery of care to the good doctors, nurses, mental health providers, and ancillary practitioners.

Good article, Wendell!

"Moral Injury" does not resonate with me. It sounds academic. It does not create the rage which should be created by the current mess.