Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) have been under scrutiny lately for their actions as middlemen in the flow of prescription drugs from manufacturers to patients. But perhaps their worst actions are buried within a maze of consolidation and paperwork. Big Insurance has consolidated the entire pharmaceutical benefit, claim, and dispensing sector to squeeze as much money out of patients as possible.

How have they pulled this off? Using the example of the insurance company Aetna, the PBM CVS Caremark, and CVS Pharmacy, all of which are owned by CVS Health, let's examine a patient filling a prescription for cancer drugs. This patient has an Aetna insurance plan that comes with PBM services provided by CVS Caremark. The patient goes to a CVS store to fill a prescription for Imatinib, a generic chemotherapy drug. The total cost the patient and insurance company pay is $17,710.21 for a 30-day supply.

But guess what. As the House Oversight and Reform Committee found, Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs only charges $72.20 for a 30-day supply of the same drug.

Cost Plus Drugs sells drugs at their wholesale price plus a 15% fee, whereas CVS Health manipulates the price and sells drugs for much more. In the case of our example patient, CVS Health can record that it paid a medical claim cost of $17,710.21 when in reality the cost to acquire the drug was below $70 and the remaining $17,640 is retained as profits disguised as medical costs. This helps CVS hide profits from regulations that require them to spend premium dollars on medical care.

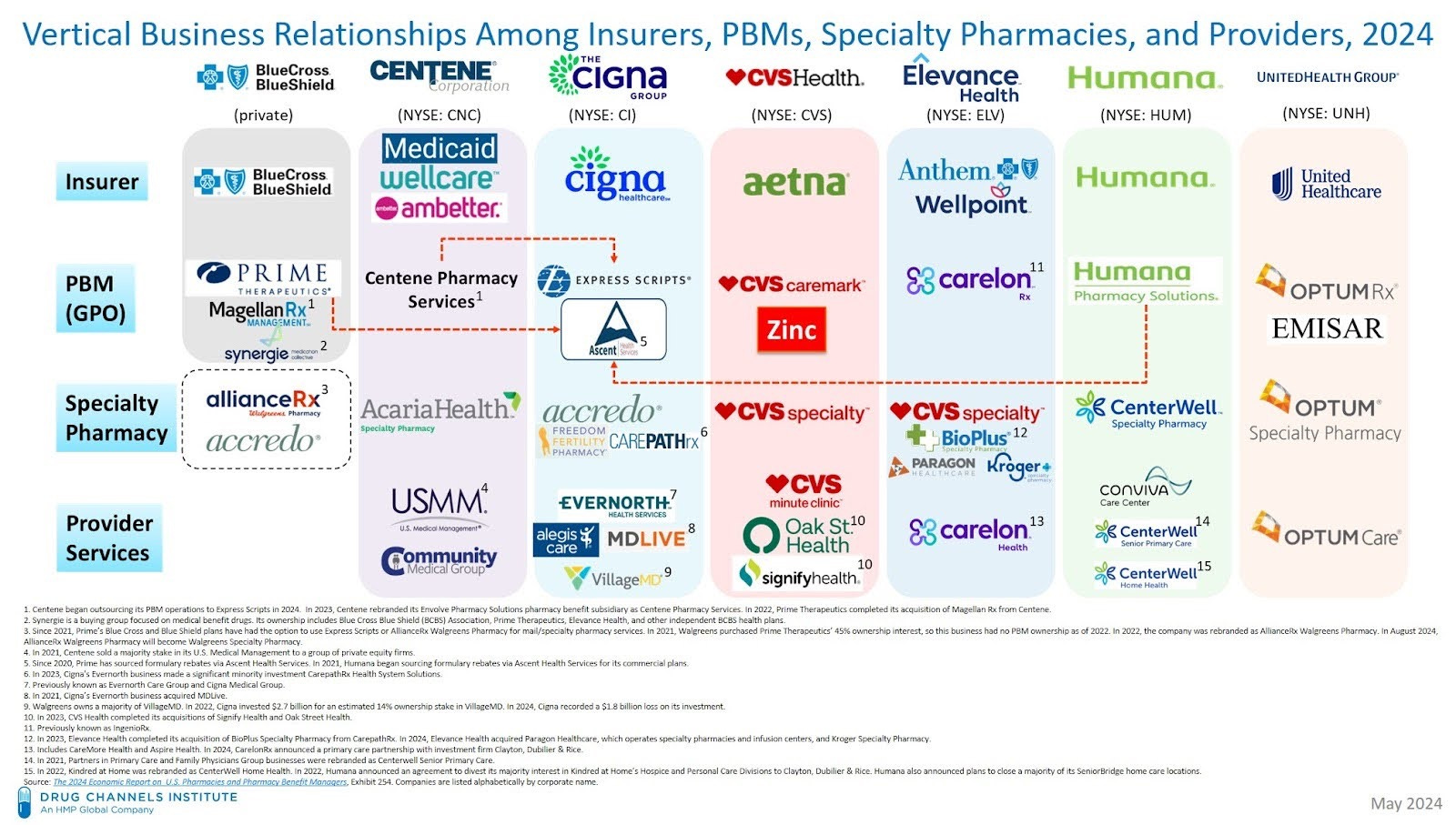

To understand this shell game, first we need to examine how interconnected Big Insurance, PBMs, and pharmacies – especially those they own – have become. Most of the largest private insurance corporations have established their own PBMs or merged with existing PBMs, including BlueCross BlueShield, Centene, Cigna, Aetna/CVS, Elevance, Humana, and UnitedHealth. All of these insurers then acquired or opened their own retail, mail-order, or specialty pharmacies. What drove this extensive consolidation? It was likely a little-known and understood piece of the Affordable Care Act that addresses something called the medical loss ratio (MLR).

The MLR is the ratio of money from premiums that people pay to insurers that goes toward direct medical care and quality improvement. By law, 80% of premium dollars in small group plans and 85% of premium dollars in large group plans must go toward medical claims costs. This regulation was designed to ensure that big insurers actually pay for the medical care they are contracted to provide, or at least that it was intended to. Big Insurance has found many ways around these regulations, including using PBMs to create a shell game.

One way PBMs make their profits is through spread pricing in which a PBM charges a higher cost to the insurer for the drug claim than the cost for the pharmacy to get the drug. PBMs often keep this “spread” as profits.

These profits are often reported as administrative expenses, not claims costs, when calculating an MLR if the insurer, PBM, and pharmacy are not jointly owned. However, in the case that the PBM owns the pharmacy, the spread (profits) are considered medical claims costs since the pharmacy/PBM is the provider of services. So, in the example above, since CVS owns the PBM and the pharmacy, the entire $17,710.21 is recorded as a medical claims expense in the MLR for a drug that only costs around $70.

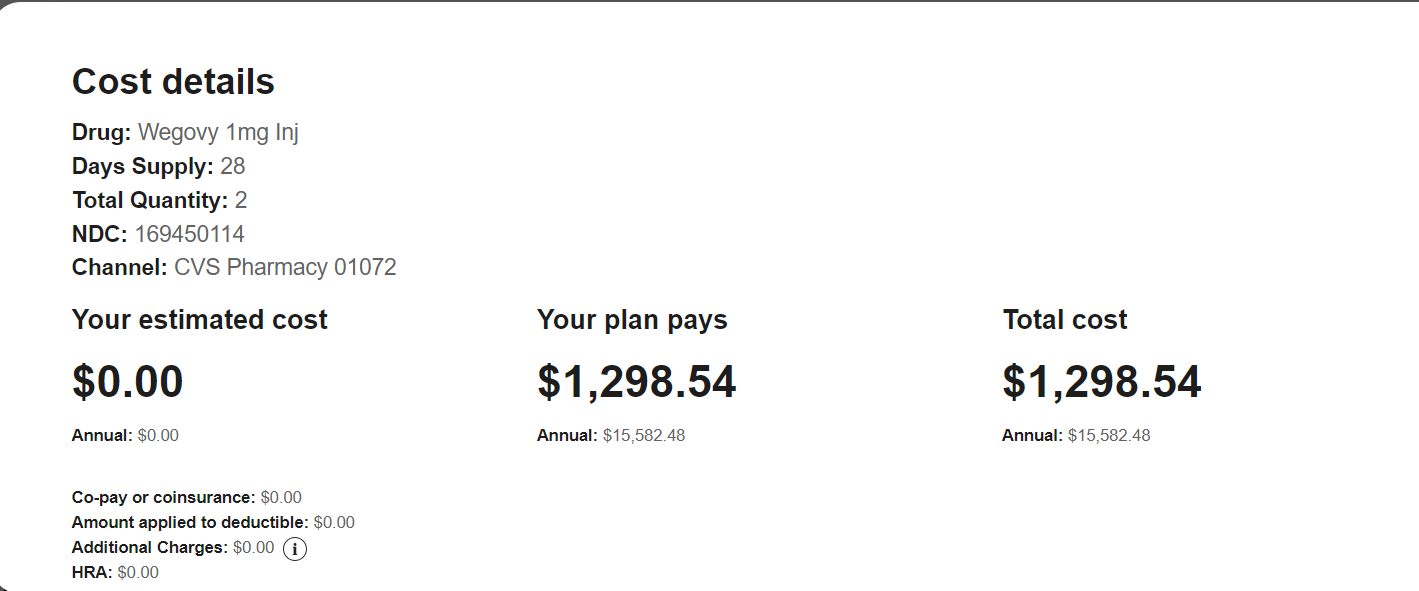

Big Insurance has seen another opportunity to run this scheme on Wegovy, the blockbuster drug used to treat obesity and reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, heart attack and stroke. The wholesale price of Wegovy in the U.S., as reported by the manufacturer Novo Nordisk, is $674.51 for a 30-day supply at a standard dosage (2 pens). [One could certainly argue that this price is already set too high by the manufacturer.] The total cost for a 30-day supply of Wegovy for a patient with Aetna insurance and the CVS Caremark PBM who fills the prescription at a CVS Pharmacy is $1298.54. This means that Aetna can report a medical claims cost of $1298.54 despite Wegovy only costing $674.51, thus disguising $624.03 of profits as medical claim costs per month per patient on Wegovy. If just 1,000 people with Aetna insurance take Wegovy for one year, Aetna would be able to hide close to $7.5 million in profits from gaming the MLR regulations.

The schemes concocted by Big Insurance are increasingly complex, but it is vital to understand them if we have any hope of lowering health care costs. In this case, PBMs mark up prescription drugs by huge margins and then charge these high prices to health insurers, our employers, government programs, and patients. The insurers don't mind paying these high prices because they own the PBMs and pharmacies and are simply moving the money from one pocket to another and sharing their spoils with their shareholders, which, by the way, include their top executives.

While moving the money around this way, they can obscure this profiteering and are able to spend less of patients’ premium dollars on care and more on profits, CEO compensation, stock buybacks, and dividends than Congress intended. This scheme also hurts patients by increasing their out-of-pocket costs since they are often responsible for a percentage of the marked-up drug price.

The games Big Insurance plays with patients’ health and money have deadly consequences and they must be stopped.

The wholesale cost of Wegovy for independent pharmacies is over $1300. We usually dispense at a lose on these medications. The wholesalers are also players in this veiled system that needs scrutiny.

A month's supply of Wegovy is four pens. You left out that we are FORCED to use the PBMs or be penalized for using other pharmacies by way of higher prices. After 30 years of being screwed by all of these companies, I could write a book on this topic.

Electeds and the FTC haul these companies in front of hearings every few years (performative) and then walk away and do nothing except complain that the cost of care / medicines is too high. I don't expect anything to be done as long as Citizen's United exists and politicians can still invest in the very companies they oversee.