How the nursing home lobby uses it's political prowess to kill would-be regulations and line the industry's pockets

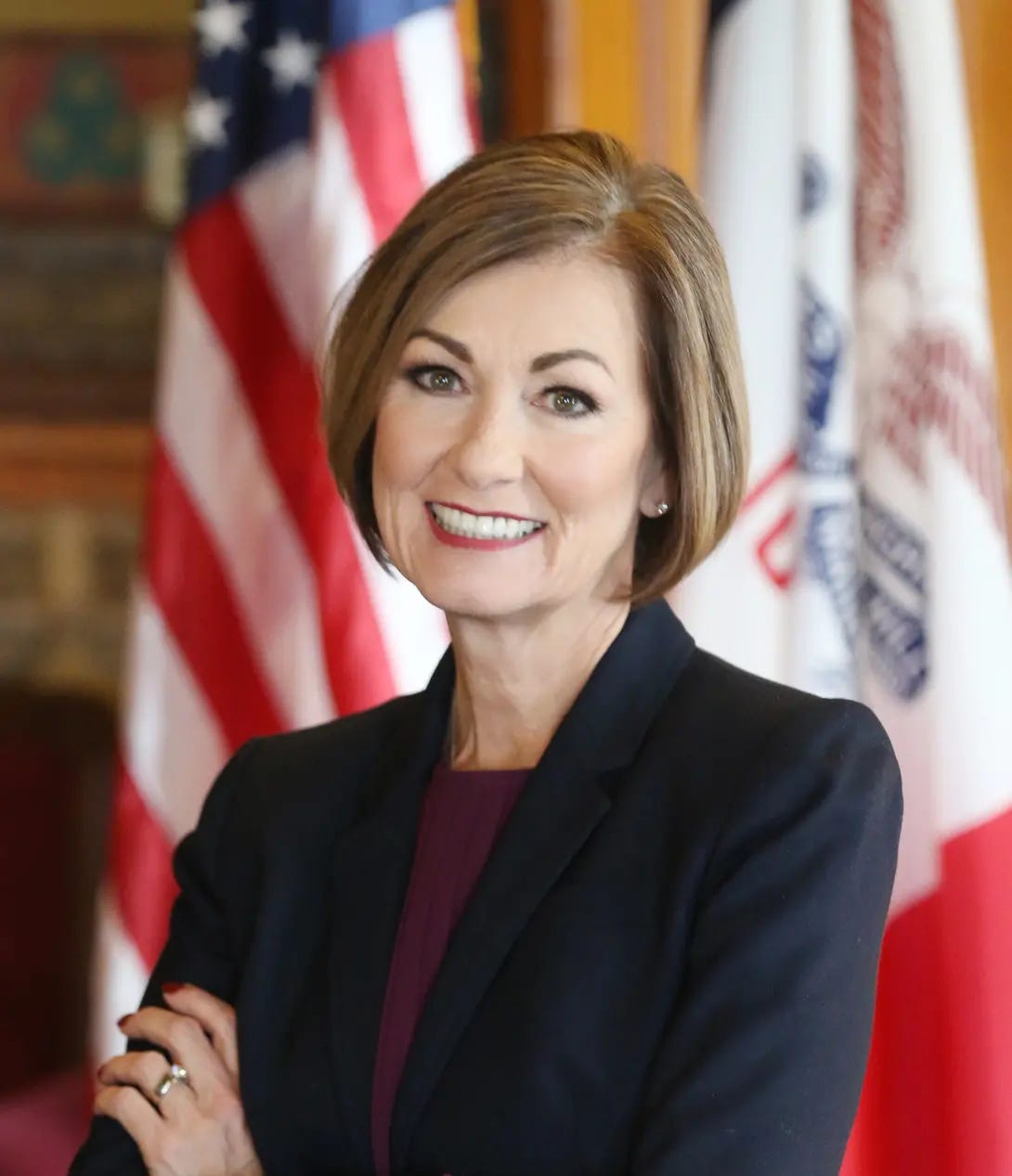

A thoroughly researched story about the Iowa nursing home lobby in the Iowa Capital Dispatch reveals the lobby’s cozy relationship with state officials, including Gov. Kim Reynolds.

Clark Kauffman, a reporter for the Dispatch, which describes itself as a “hard-hitting, independent news organization,” begins his story with the governor’s speech to nursing home executives who had given her some $80,000 in contributions for her 2022 reelection campaign, an amount collected just in the previous four weeks. A chummy relationship between state government officials and the nursing home industry may not be news in this country, but Kauffman’s meticulous reporting and connecting of dots make this piece required reading for Iowans facing a nursing home placement for a relative and for reporters across the country who might find similar situations in their regions.

I have written many nursing home stories over the years and so have other journalists who are readers of this newsletter, but I have never seen such brazen admissions by elected officials who are supposed to represent the public interest and instead overtly side with those representing private interests.

In her prepared remarks, the governor didn’t leave any ambiguity about whose side she was on, and Kauffman’s reporting shows she is not on the side of residents who have received bad or questionable care and their families who seek redress. The governor reminded the assembled nursing home executives of her efforts to loosen “regulatory barriers” and shield those companies from legal liability resulting from wrongful death claims and other lawsuits.

“You’re not getting much help from the federal government, which apparently has never seen something it doesn’t like to regulate or mandate,” she told industry representatives. “I can’t control Washington’s approach, but I can promise this: In Iowa, you’ll continue to get the support you’re being denied in Washington.”

What makes Kauffman’s story such a stand out is that he captured the unabashed money flow from the industry to the state’s politicians eager to take it. The Iowa Capital Dispatch reviewed legislation, federal tax returns, campaign contributions, inspection reports and audio recordings of industry lobbyists that reveal a tale of money and influence that affect the care received by elderly and disabled people in the state.

Here’s what we already know

In its examination of the records, the Dispatch found that in 2021 the state bestowed the Governor’s Award for Quality Care to Accura HealthCare’s nursing home in Stanton, Iowa. Two months after the award was announced, state inspectors cited the home for placing residents in “immediate jeopardy,” a very serious violation. It seems a defective door alarm enabled a resident to leave the facility and walk about one-third of a mile and cross a busy street before being spotted. Kauffman reported that the Accura chain has been hit with more than $1.1 million in fines for quality of care violations.

Kauffman got to the heart of the nursing home industry’s coziness with state officials, noting that state records show the Iowa Health PAC, the political action committee of the Iowa Health Care Association, which represents the state’s long-term care facilities, has spent $1,493,612 on campaign donations and related expenses since 2016. The governor, Kauffman reported, collected $132,785 of that money and noted that amount was more than she received from other Iowa PACs such as those representing the Farm Bureau, banks and gun owners, all important special interest groups in rural states.

Kauffman interviewed a consultant and advocate for the state’s older residents, John Hale, who told him the industry makes “big campaign contributions, gives out nice awards and regularly hobnobs with elected officials to get what they want – which is $800 million taxpayer dollars flowing to nursing home owners and operators annually with no expectations for how the dollars are used and no questions asked about what they accomplish.”

Hale told Kauffman, “At the Iowa Capitol, money buys influence. The system is corrupt and broken.”

His remarks could apply to the power of the nursing home lobby in other states as well. One point Kauffman exposes is that a lot of the money spent on lobbying and buying influence actually comes from the government itself. Kauffman reported that Dean Lerner, who headed the state inspections agency in a Democratic administration, has “long complained that the money the industry spends lobbying state legislators originates with taxpayers.”

Here’s how: Nursing homes get most of their income from Medicaid, which pays for huge amounts of residents’ care. They then pay the industry’s chief lobbying group, the Iowa Health Care Association, $2.3 million in annual dues, while the association pays its CEO and lobbyists some $1.2 million a year.

Kauffman also looked at the results of this broken regulatory system for some of the state’s sickest and most vulnerable people. The attempt to get cameras or “granny cams” in residents’ rooms demonstrates the near absolute power of the state’s nursing home industry. Such cameras would allow families to watch what was happening in their loved one’s rooms. Kauffman reported that during the 2023 legislative session, Merea Bentrott, a lobbyist for the Iowa Health Care Association, gave a revealing report to the state’s nursing home owners that “sheds considerable light on the industry’s efforts to kill legislation that would have prevented nursing homes from refusing to let the families of residents put surveillance-style cameras in the rooms of their loved ones.” During another Zoom call, Kauffman reported, Bentrott warned nursing home executives the push to put cameras in residents’ rooms was likely to come up again. “This is something that will probably come up every single year,” she said. “Best case scenario is that we kill it before it even gets any legs,” And kill it they did.

A clarion call for reform

Kauffman’s revelations about the politics of Iowa’s nursing home lobby and the clout it has in stopping legislation that could improve the lives of Iowans in the state’s nursing facilities deserve emulation by other reporters.

Christopher Rowland of the Washington Post examined a vastly underreported aspect of aging and the lack of suitable housing for countless older Americans living on the streets and in shelters. He reported that many “long-term chronically ill people are simply aging on the street,” and I reported that “housing solution gives a new meaning to “aging in place,” a goal that surfaced years ago intended to keep seniors in their homes as long as possible.

Both stories raise an important question that has been asked for decades now: Is that what America wants for its senior citizens?

We are falling far behind peer nations like Japan, Germany, Denmark, France and Canada, which have done much more to house and care for their oldest and most vulnerable citizens. I discussed this with Katie Sloan who heads LeadingAge, the association of nonprofit providers of aging services that includes nursing homes, home health, hospice, adult day providers as well as independent (including affordable housing for low-income older adults), assisted and senior living communities. Why has the press coverage of this topic over the years failed to spark a national outrage about how our oldest and most vulnerable citizens are faring in the country’s nursing homes and on the streets where too many now live? Why hasn’t more progress been made in improving long-term care?

Sloan, whose trade group recognizes the problem, says, “There is so much denial about aging. We have under-valued older adults and have written them off. We don’t respect them and their agency. We have not sounded a call to action for them.

It’s a catastrophe waiting to happen.” The U.S. is not regulating to facilitate quality but to punish bad actors. Another big difference, she pointed out, is that other countries consider long-term care part of the social care agenda. In the U.S., it is medicalized, considered part of health care, she explained.

“We’re facing some real problems with access to services,” Sloan said “Waiting lists are long and residents may have to go to another state to find care. The access issue becomes problematic. It’s a clarion call, and in rural America care is problematic.”

And that brings me back to Iowa, where the nursing home lobby has a stranglehold on the legislature and bills that might help improve care. It is a dilemma America has yet to solve.

Nursing home executives are somewhere near the top of my list of sub-human life forms.

Wow.